Texas et al. v. BlackRock, Inc. et al.

INTRODUCTION 1. For the past four years, America’s coal producers have been responding not to the price signals of the free market, but to the commands of Larry Fink, BlackRock’s Chairman and CEO, and his fellow asset managers. As demand for the electricity Americans need to heat their homes and power their businesses has gone […]

This post provides the text of the complaint filed November 27, 2024 by the attorney generals of Texas and 10 other states against BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street, State of Texas/Ken Paxton Aty General et al v. BlackRock, Inc. et al, Docket No. 6:24-cv-00437 (E.D. Tex. Nov 27, 2024).

INTRODUCTION

1. For the past four years, America’s coal producers have been responding not to the price signals of the free market, but to the commands of Larry Fink, BlackRock’s Chairman and CEO, and his fellow asset managers. As demand for the electricity Americans need to heat their homes and power their businesses has gone up, the supply of the coal used to generate that electricity has been artificially depressed—and the price has skyrocketed. Defendants have reaped the rewards of higher returns, higher fees, and higher profits, while American consumers have paid the price in higher utility bills and higher costs.

2. Over a century ago, Congress enacted Section 7 of the Clayton Act to prohibit any acquisition of stock where “the effect of such acquisition may be substantially to lessen competition.” 15 U.S.C. § 18. Congress recognized that when an investor brings “under one control the competing companies whose stock it has thus acquired,” it achieves what is in substance a mere “incorporated form of the old-fashioned trust.” H.Rep. No. 627, 63rd Cong., Second Sess., at 17 (May 6, 1914). Such anticompetitive ownership blocks are “an abomination,” and the federal antitrust laws absolutely prohibit them. Id.

3. Defendants are three of the largest institutional investors in the world. Each Defendant has individually acquired substantial stockholdings in every significant publicly held coal producer in the United States. Each has thereby acquired the power to influence the policies of these competing companies and bring about a substantial lessening of competition in the markets for coal. And each has used its power to affect a substantial reduction in competition in coal markets. Considered alone and in isolation, each Defendant’s acquisition and use of shareholdings in the domestic coal producers has violated Section 7 of the Clayton Act.

![]()

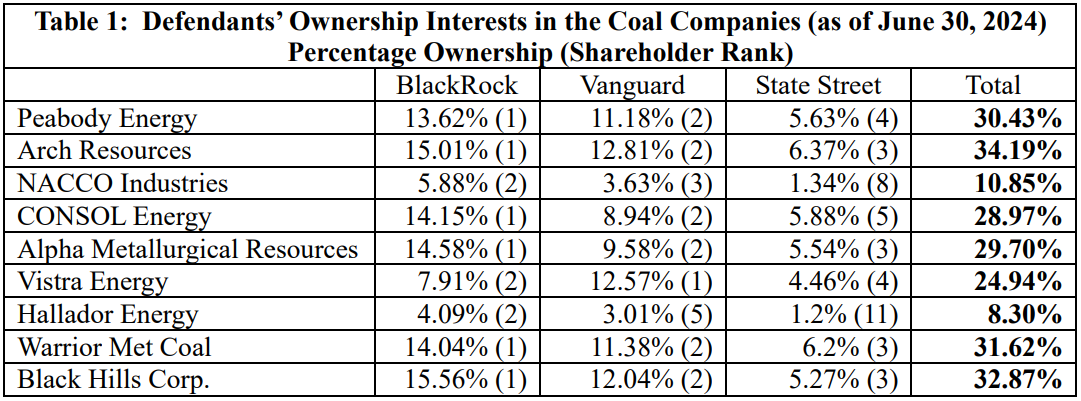

4. But Defendants have not just acted alone and in isolation. In 2021, they went further. In that year, Defendants each publicly announced their commitment to use their shares to pressure the management of all the portfolio companies in which they held assets to align with net- zero goals. Those goals included reducing carbon emissions from coal by over 50%. Rather than individually wield their shareholdings to reduce coal output, therefore, Defendants effectively formed a syndicate and agreed to use their collective holdings of publicly traded coal companies to induce industry-wide output reductions. To be sure, earlier this year BlackRock and State Street publicly proclaimed that they withdrew from one of the organizations that they previously used to coordinate their anticompetitive conduct, Climate Action 100+. But formal withdrawal from that one organization does not change the reality that Defendants’ holdings threaten to substantially reduce competition in violation of Section 7 of the Clayton Act. Nor does it negate the ongoing and future threat of Defendants’ coordinated anticompetitive conduct or absolve Defendants of their legal liability for past violations. Below is a table showing Defendants’ collective ownership stake in the publicly traded domestic coal producers (hereinafter, the “Coal Companies”), of which Arch Resources and Peabody Energy are by far the largest—responsible for, respectively, 17.2% and 13.2% of all coal produced in the United States:

| Peabody Energy | 30.43% |

| Arch Resources | 34.19% |

| NACCO Industries | 10.85% |

| CONSOL Energy | 28.97% |

| Alpha Metallurgical Resources | 29.7% |

| Vistra Energy | 24.94% |

| Hallador Energy | 8.3% |

| Warrior Met Coal | 31.62% |

| Black Hills Corporation | 32.87% |

5. Defendants have immense influence over these companies on their own, but collectively Defendants possess a power to coerce management that is all but irresistible. Defendants have used that collective power—by proxy voting and otherwise—to pressure the major coal producers to reduce production of coal, and in particular production of the thermal coal used to generate the electricity that powers American homes and businesses. The publicly traded coal producers have responded to Defendants’ influence by reducing their output, even as coal prices have risen significantly. At the same time, privately held coal producers in which Defendants have no ownership stake have been unable to increase their production sufficiently to meet demand and capture greater market share. Some of these producers are smaller firms that lack the proven reserves, the financial wherewithal, and production capacity that they would need to raise production; still others are unable to obtain financing from banks and financial institutions that have been pressured to cut off the funding that the coal industry would need to expand capacity and raise output. Defendants are directly restraining competition between the companies whose shares they have acquired, but their war on competition has consequences for the entire industry.

6. Defendants have leveraged their holdings and voting of shares to facilitate an output reduction scheme, which has artificially constrained the supply of coal, significantly diminished competition in the markets for coal, increased energy prices for American consumers, and produced cartel-level profits for Defendants. Defendants’ acquisition and use of their shareholdings thus violated both Section 7 of the Clayton Act and State antitrust laws, while Defendants’ formation of an output-reduction syndicate that yielded supra-competitive profits for themselves and their portfolios violated Section 1 of the Sherman Act and State antitrust laws.

7. Defendants have publicly defended their anticompetitive scheme with appeals to environmental stewardship. But acquiring shares of common stock, “the effect of which ‘may be substantially to lessen competition’ is not saved because, on some ultimate reckoning of social or economic debits and credits, it may be deemed beneficial.” United States v. Phila. Nat’l Bank, 374 U.S. 321, 371 (1963). The nation’s antitrust laws “reflect[] a legislative judgment that ultimately competition will produce not only lower prices, but also better goods and services.” Nat’l Soc’y of Pro. Eng’rs v. United States, 435 U.S. 679, 695 (1978). Defendants’ belief that concern for the climate confers a license to suppress competition is “mistaken. The antitrust laws don’t permit [the enforcers of America’s antitrust laws] to turn a blind eye to an illegal deal just because the parties commit to some unrelated social benefit.”1 Under the antitrust laws, full and open competition must dictate domestic coal production.

8. In addition to joining with the other two major institutional asset managers to bring about a reduction in the output of coal, Defendant BlackRock went further—actively deceiving investors about the nature of its funds. Rather than inform investors that it would use their shareholdings to advance climate goals, BlackRock consistently and uniformly represented its non-ESG funds would be dedicated solely to enhancing shareholder value. But as detailed below, BlackRock routinely violated its pledge to investors, using all its holdings to advance its climate goals and—as most relevant here—promote the objectives of its output-reduction syndicate.

9. The American consumer is entitled to enjoy the fruits of free markets, vigorous competition, and (in the case of BlackRock) honest investment managers. Competitive markets— not the dictates of far-flung asset managers—should determine the price Americans pay for electricity. The Plaintiff States accordingly seek injunctive relief to put an end to Defendants’ illegal practices and restore free and open competition to the coal markets, as well as damages, restitution, and civil penalties.

PARTIES

Plaintiffs

10. Plaintiff States of Texas, Alabama, Arkansas, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, West Virginia, and Wyoming (collectively, “Plaintiff States”), by and through their respective Attorneys General, bring this action in their respective sovereign capacities and as parens patriae on behalf of the citizens, general welfare, and economy of their respective states under their statutory, equitable, or common law powers, and pursuant to Sections 4C and 16 of the Clayton Act, 15 U.S.C. §§ 15C & 26.

Defendants

11. Defendant BlackRock, Inc. (“BlackRock”) is a Delaware Corporation, with its principal place of business located at 50 Hudson Yards, New York, New York 10001.

12. Defendant State Street Corporation (“State Street”) is a Massachusetts Corporation with its principal place of business at One Congress Street, Boston, Massachusetts 02114.

13. The Vanguard Group, Inc. (“Vanguard”) is a Pennsylvania Corporation, with its principal place of business at 100 Vanguard Blvd., Malvern, Pennsylvania 19355.

JURISDICTION, VENUE, AND COMMERCE

14. Plaintiff States bring this action under Section 1 of the Sherman Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1, and Sections 7 and 16 of the Clayton Act, 15 U.S.C. §§ 18 and 26.

15. This Court possesses jurisdiction over the subject matter of this action under 15 U.S.C. § 4, 28 U.S.C. §1331, and 28 U.S.C. § 1337. This Court has jurisdiction over Plaintiff States’ non-federal claims under 28 U.S.C. § 1367(a), as well as under principles of supplemental jurisdiction.

16. This Court has personal jurisdiction over Defendants, each of which has minimum contacts with the United States, pursuant to 15 U.S.C. § 22; venue is proper in this District pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §§ 1391(b) & (c), because Defendants are subject to personal jurisdiction in, and thus reside in, this District, and 15 U.S.C. § 22, because Defendants transact business and are found within this District.

17. Defendants sell the financial products that they have used to accomplish their scheme throughout the United States and across state lines. Defendants are engaged in, and their activities substantially affect, interstate trade and commerce throughout the United States. Defendants’ acquisitions and use of stock have significantly lessened competition in the markets for coal throughout the United States, including sales of coal made to direct purchasers in this District. Defendants provide a range of products and services that are marketed, distributed, and offered to consumers throughout the United States, in the each of the Plaintiff States, and across state lines.

DEFENDANTS HAVE EACH ACQUIRED SUBSTANTIAL PERCENTAGES OF THE OUSTANDING SHARES OF U.S. COAL COMPANIES

18. Among coal producers responsible for more than 5 million tons of coal in 2022, eight are publicly held: Peabody Energy; Arch Resources; NACCO Natural Resources; CONSOL Energy; Alpha Metallurgical Resources; Vistra; Hallador Energy Company; and Warrior Met Coal.2 These eight firms are responsible for approximately 46% of total domestic coal production and significant shares of the domestic production of thermal coal and, along with the Black Hills Corporation, of South Powder River Basin (“SPRB”) coal.

19. As explained below, Defendants are three of the largest investors in global coal production. As of February 15, 2022, BlackRock’s total investment in coal was $108.787 billion; Vanguard’s, $101.119 billion; and State Street’s, $35.736 billion.3

20. Defendants, and their subsidiaries and affiliates, acting by and through the funds, trusts, and other investment vehicles that they manage and control, have acquired substantial shareholdings in, and have become the three largest shareholders of America’s publicly-held coal companies. See below Table 1. BlackRock is the largest shareholder of six of the nine publicly- traded coal companies (hereinafter, “the Coal Companies”), and the second largest of the remaining three.4 Vanguard is the largest shareholder of Vistra Energy, the second largest shareholder of six Coal Companies, and the third and fifth holder of, respectively, NACCO Industries and Hallador. State Street is smaller, but only in comparison to BlackRock and Vanguard; it is among the top five shareholders of all but two of the Coal Companies.

Defendants own 30.43% of Peabody Energy

21. As of June 30, 2024 Defendants owned 38,314,525 shares of Peabody Energy common stock, representing 30.43% of the company’s outstanding shares.

22. Defendant Vanguard owned 14,073,850 shares of Peabody Energy’s common stock as of June 30, 2024, representing 11.18% of the company’s outstanding shares. As of December 31, 2020, Vanguard had reported owning only 3,221,900 shares of Peabody Energy. Vanguard thus acquired 10,851,950 shares of Peabody Energy between December 2020 and June 2024.

23. Defendant BlackRock owned 17,149,187 shares of Peabody Energy’s common stock as of June 30, 2024, representing 13.62% of the company’s outstanding shares. As of December 31, 2020, BlackRock had reported owning 4,901,754 shares of Peabody Energy. BlackRock thus acquired 12,247,433 shares of Peabody Energy between December 2020 and June 2024.

24. Defendant State Street owned 7,091,488 shares of Peabody Energy’s common stock on June 30, 2024, representing 5.63% of the company’s outstanding shares. As of December 31, 2020, State Street had held 1,730,727 shares of Peabody Energy. State Street thus reported acquiring 5,360,761 shares of Peabody Energy’s common stock between December 2020 and June 2024.

Defendants own 34.19% of Arch Resources

25. As of June 30, 2024, Defendants owned 6,183,333 shares of Arch Resources’ Class A common stock,5 representing 34.19% of the company’s outstanding shares.

26. Defendant Vanguard owned 2,316,930 shares of Arch Resources’ Class A common stock on June 30, 2024, representing 12.81% of the company’s outstanding shares. On December 31, 2020, Vanguard reported owning 1,407,442 shares of Arch Resources. Vanguard thus acquired 909,488 shares between December 2020 and June 2024.

27. Defendant BlackRock owned 2,713,914 shares of Arch Resources’ Class A common stock as of June 30, 2024, representing 15.01% of the company’s outstanding shares. As of December 31, 2020, BlackRock reported owning 1,111,103 shares of Arch Resources. BlackRock thus acquired 1,602,811 shares between December 2020 and June 2024.

28. Defendant State Street held 1,152,489 shares of Arch Resources’ Class A common stock on June 30, 2024, representing 6.37% of the company’s outstanding shares. As of December 31, 2020, State Street reported owning 1,203,281 shares of Arch Resources. State Street thus sold 50,792 shares of Arch Resources Class A common stock between December 2020 and June 2024.

Defendants own 10.85% of NACCO Industries

29. As of June 30, 2024, Defendants held 627,992 shares of NACCO’s Class A common stock, representing 10.85% of the company’s publicly-held outstanding shares. NACCO’s Class B common stock is not publicly traded. Each share of Class B Common Stock is entitled to ten votes; otherwise, Class A and Class B common stock are equal in respect of rights to dividends and any other distributions in cash, stock, or property of the Company.6

30. Defendant Vanguard owned 209,995 shares of NACCO’s common stock as of June 30, 2024, representing 3.63% of the company’s outstanding shares. Vanguard reported owning 231,908 shares of NACCO’s common stock as of December 31, 2020.

31. Defendant BlackRock held 340,484 shares of NACCO’s common stock as of June 30, 2024, representing 5.88% of the company’s outstanding shares. On December 31, 2020, BlackRock had owned 268,719 shares of NACCO’s common stock. BlackRock thus acquired 71,765 shares of NACCO’s common stock between December 2020 and June 2024.

32. Defendant State Street held 77,513 shares of NACCO’s common stock as of June 30, 2024, representing 1.34% of the company’s outstanding shares. State Street reported owning 80,522 shares of NACCO’s common stock as of December 30, 2020.

Defendants own 28.97% of CONSOL Energy

33. As of June 30, 2024, Defendants held 8,517,992 shares of CONSOL Energy’s common stock, representing 28.97% of the company’s outstanding shares.

34. Defendant Vanguard held 2,628,383 shares of CONSOL Energy’s common stock as of June 30, 2024, representing 8.94% of the company’s outstanding shares. As of December 31, 2020, Vanguard reported owning 1,444,540 shares of CONSOL Energy’s common stock. Vanguard thus acquired 1,183,843 shares of CONSOL Energy between December 2020 and June 2024.

35. Defendant BlackRock held 4,159,982 shares of CONSOL Energy’s common stock as of June 30, 2024, representing 14.15% of the company’s outstanding shares. On December 31, 2020, BlackRock had reported owning 4,491,811 shares of CONSOL Energy’s common stock.

36. Defendant State Street held 1,729,627 shares of CONSOL Energy’s common stock as of June 30, 2024, representing 5.88% of the company’s outstanding shares. As of December 31, 2020, State Street reported owning 780,949 shares of CONSOL Energy. State Street thus acquired 948,678 shares of CONSOL Energy’s common stock between December 2020 and June 2024.

Defendants own 29.7% of Alpha Metallurgical Resources

37. As of June 30, 2024, Defendants held 3,866,622 shares of Alpha Metallurgical Resources’ common stock, representing 29.7% of the company’s outstanding shares.

38. Defendant Vanguard held 1,247,439 shares of Alpha Metallurgical Resources’ common stock as of June 30, 2024, representing 9.58% of the company’s outstanding shares. As of December 31, 2020, Vanguard reported owning 843,983 shares of Contura Energy Inc.’s common stock. 7 Vanguard thus acquired 403,456 shares of Alpha Metallurgical Resources between December 2020 and June 2024.

39. Defendant BlackRock held 1,897,483 shares of Alpha Metallurgical Resources’ common stock as of June 30, 2024, representing 14.58% of the company’s outstanding shares. BlackRock reported owning 1,465,696 shares of Contura Energy, Inc., on December 31, 2020. BlackRock thus acquired 431,787 shares of Alpha Metallurgical Resources’ common stock between December 2020 and June 2024.

40. Defendant State Street held 721,700 shares of Alpha Metallurgical Resources’ common stock as of June 30, 2024, representing 5.54% of the company’s outstanding shares. State Street did not report owning any shares of Contura Energy Inc. on December 31, 2020. State Street thus acquired 721,700 shares of Alpha Metallurgical Resources’ common stock between December 2020 and June 2024.

Defendants own 24.94% of Vistra Energy

41. As of June 30, 2024, Defendants held 85,652,222 shares of Vistra’s common stock, representing 24.94% of the company’s outstanding shares.

42. Defendant Vanguard held 43,173,721 shares of Vistra’s common stock as of June 30, 2024, representing 12.57% of the company’s outstanding shares. On December 31, 2020, Vanguard reported owning 46,057,648 shares of Vistra’s common stock.

43. Defendant BlackRock held 27,160,648 shares of Vistra’s common stock as of June 30, 2024, representing 7.91% of the company’s outstanding shares. On December 30, 2020, BlackRock reported owning 28,579,182 shares of Vistra’s common stock.

44. Defendant State Street held 15,317,853 shares of Vistra’s common stock as of June 30, 2024, representing 4.46% of the company’s outstanding shares. On December 31, 2020, State Street reported owning 9,290,171 shares of Vistra’s common stock. State Street thus acquired 6,027,682 shares of Vistra’s common stock between December 2020 and June 2024.

Defendants own 8.3% of Hallador Energy

45. As of June 30, 2024, Defendants held 3,540,921 shares of Hallador Energy’s common stock, representing 8.3% of the company’s outstanding shares.

46. Defendant Vanguard held 1,281,063 shares of Hallador Energy’s common stock as of June 30, 2024, representing 3.01% of the company’s outstanding shares. On December 31, 2020, Vanguard reported owning 704,524 shares of Hallador Energy’s common stock. Vanguard thus acquired 576,539 shares of Hallador Energy’s common stock between December 2020 and June 2024.

47. Defendant BlackRock held 1,742,499 shares of Hallador Energy’s common stock as of June 30, 2024, representing 4.09% of the company’s outstanding shares. On December 31, 2020, BlackRock reported owning 101,138 shares of Hallador Energy’s common stock. BlackRock thus acquired 1,641,361 shares of Hallador Energy’s common stock between December 2020 and June 2024.

48. Defendant State Street held 517,359 shares of Hallador Energy’s common stock as of June 30, 2024, representing 1.2% of the company’s outstanding shares. State Street reported not owning any shares of Hallador Energy as of December 31, 2020. State Street thus acquired 517,359 shares of Halldor Energy’s common stock between December 2020 and June 2024.

Defendants own 31.62% of Warrior Met Coal

49. As of June 30, 2024, Defendants held 16,543,426 shares of Warrior Met Coal’s common stock, representing 31.62% of the company’s outstanding shares.

50. Defendant Vanguard held 5,952,261 shares of Warrior Met Coal’s common stock as of June 30, 2024, representing 11.38% of the company’s outstanding shares. As of December 31, 2020, Vanguard reported owning 5,224,538 shares of Warrior Met Coal common stock. Vanguard thus acquired 727,723 shares of Warrior Met Coal’s common stock between December 2020 and June 2024.

51. Defendant BlackRock held 7,345,650 shares of Warrior Met Coal’s common stock as of June 30, 2024, representing 14.04% of the company’s outstanding shares. BlackRock reported holdings of 7,184,086 shares of Warrior Met Coal’s common stock as of December 31, 2020. BlackRock thus acquired 161,564 shares of Warrior Met Coal’s common stock between December 2020 and June 2024.

52. Defendant State Street held 3,245,515 shares of Warrior Met Coal’s common stock as of June 30, 2024, representing 6.2% of the company’s outstanding shares. On December 31, 2020, State Street reported owning 3,725,752 shares of Warrior Met Coal.

Defendants own 32.87% of Black Hills Corporation

53. As of June 30, 2024, Defendants held 22,925,181 shares of Black Hills Corporation common stock, representing 32.87% of the company’s outstanding shares.

54. Defendant Vanguard held 8,394,948 shares of Black Hills Corporation common stock as of June 30, 2024, representing 12.04% of the company’s outstanding shares. On December 31, 2020, Vanguard reported owning 6,576,633 shares of Black Hills Corporation’s common stock. Vanguard thus acquired 1,818,315 shares of Black Hills Corporation’s common stock between December 2020 and June 2024.

55. Defendant BlackRock held 10,851,268 shares of Black Hills Corporation common stock as of June 30, 2024, representing 15.56% of the company’s outstanding shares. As of December 31, 2020, BlackRock reported owning 8,581,943 shares of Black Hills Corporation’s common stock. BlackRock thus acquired 2,269,325 shares of Black Hill Corporation common stock between December 2020 and June 2024.

56. Defendant State Street held 3,678,965 shares of Black Hills Corporation common stock as of June 30, 2024, representing 5.27% of the company’s outstanding shares. As of December 31, 2020, State Street reported owning 5,538,442 shares of Black Hill Corporation’s common stock.

57. Defendants’ acquisitions have made each of them a substantial shareholder in each of the nation’s major coal miners. This concentrated ownership of horizontal competitors poses a significant threat to competition in the markets for coal. It is precisely these types of threat to competition that Section 7 was enacted to thwart “in their incipiency.” United States v. DuPont, 353 U.S. 586, 597 (1957).

THE RELEVANT MARKETS

58. There are clear and readily defined coal markets—the markets in which Defendants’ acquisitions of shares have threatened to impair and have in fact impaired competition.

59. As detailed further below, there are two relevant product markets for coal. They are:

a. The market for South Powder River Basin Coal, which is the preferred coal for power plants as its inherent properties ease regulatory compliance and enhance operational efficiency. Defendants own 30.43%, 34.19%, and 32.87% of the three publicly traded companies that produce South Powder River Basin Coal. Those companies control 63.5% of the market in South Powder River Basin Coal.

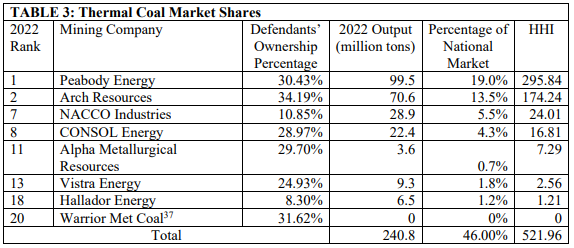

b. The market for Thermal Coal, which is burned to generate steam to produce electricity or for process heating purposes. Defendants own between 8.3% and 34.19% of the eight publicly traded companies listed above that produce Thermal Coal. These companies control 46% of the market in Thermal Coal.

60. As detailed further below, there are multiple potentially relevant geographic markets for coal. They are:

a. The South Powder River Basin—the sole source for South Powder River Basin coal and thus the only place purchasers can obtain such coal.

b. The United States—the domestic coal market cannot source coal from abroad without incurring significant transportation costs.

c. The locations where South Power River Basin coal is consumed—nearly all such coal is burned at the 150 power plants located throughout the United States

61. Six of those plants are located in the State of Texas: the Welsh Power Plant, located in Cason, TX8 ; the Fayette Power Project, located in La Grange, TX9 ; Harrington Generating Station, located near Amarillo, TX10; Tolk Station, located in Muleshoe, TX11; W.A. Parish Generating Station, located near Thompsons, TX12; and the Limestone Power Plant, located in Jewett, TX.13

The Specific Characteristics of Coal Determine Its Uses

62. Consumers of coal are constrained in the types of coal they can consume given the nature of their industrial processes, the design specification of their facilities and equipment, and the characteristics of the coal suited to those processes. Both the classification of, and the definitions of the relevant markets for coal depend on its characteristics and its point of origin.

63. Heat value, sulfur content, ash, moisture content, and volatility are important variables in the marketing and use of coal. Heat value refers to the coal’s energy content and depends on the carbon content of the coal; it is measured in British Thermal Units. Sulfur content determines the amount of sulfur dioxide that will be produced in combustion and affects the ability of coal-fueled power plants to comply with applicable federal and state emissions standards. Ash content is an important characteristic because it impacts boiler performance, and because of the added costs to the electric generating plants that must handle and dispose of ash following combustion. A high moisture content will decrease heat value and increase the weight of the coal, making it a less efficient source of energy and more expensive to transport. Volatility and other characteristics, including fluidity and swelling capacity, are particularly important for users of the metallurgical coal that is used to produce coke.

64. Coal is generally classified into four categories: lignite, subbituminous, bituminous, and anthracite. These classifications reflect the amount of carbon the coal contains and the amount of heat energy it can produce.

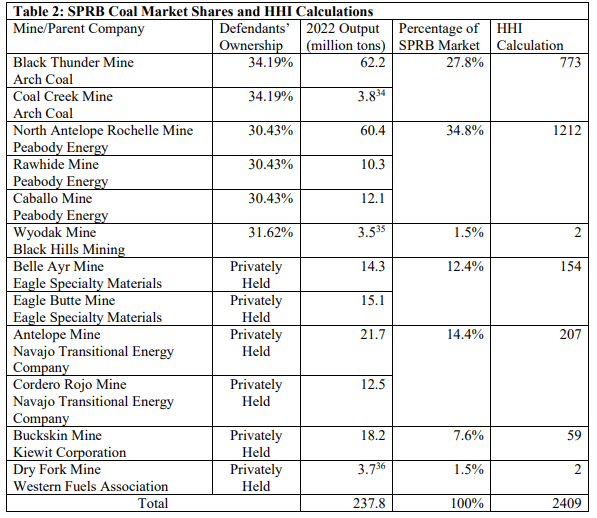

a. Anthracitic coal contains >86% carbon and has a high heat value. It is mined in northeastern Pennsylvania, and accounted for less than 1% of the coal mined in the United States in 2022. It is primarily used in the metallurgy and steel-making industries. 14

b. Bituminous coal contains 45%-86% carbon and is the most abundant class of coal found in the United States, accounting for about 46% of total U.S. production in 2022. It is used to generate electricity and is an important raw material for making coke for the iron and steel industry. The top five bituminous producing states and their percentage share of total U.S. bituminous production in 2022 were: West Virginia, 31%; Illinois, 14%; Pennsylvania, 14%; Kentucky, 11%; and Indiana, 9%.15

c. Subbituminous coal contains 35%–45% carbon and has a lower heat value than bituminous coal. In 2022, subbituminous coal accounted for approximately 46% of total U.S. coal production. The five subbituminous producing states and their percentage share of total U.S. subbituminous production in 2022 were: Wyoming, 89%; Montana, 8%; New Mexico, 2%; Colorado, 2%; and Alaska, <1%.16 South Powder River Basin coal is subbituminous coal.17 Its friable nature makes it well suited for modern pulverized coal power plants.

d. Lignite contains 25%–35% carbon and has the lowest energy content of all coal ranks. Lignite is crumbly and has high moisture content, which contributes to its low heating value. In 2022, five states produced lignite, which accounted for 8% of total U.S. coal production: they were: North Dakota, 56%; Texas, 36%; Mississippi, 7%; Louisiana, 1%; and Montana, <1%.18 Most lignite is used as thermal coal. Due to its high moisture content and low BTU value, shipping lignite long distances is not feasible. Consequently, it is burned near where it is mined.19

The Relevant Product Markets

65. Defendants have sought and continue to seek to reduce the production of coal across the board. Because of the market-wide impact of their holdings, Defendants’ acquisitions of stock and their use of those shares has significantly lessened competition across all coal markets. Plaintiff States have nevertheless identified the following relevant antitrust product and geographic markets in which Defendants’ acquisitions may have the effect of significantly lessening competition and indeed have substantially lessened competition.

There is a Relevant Product Market for South Powder River Basin Coal

66. The Powder River Basin (“PRB”) is in northeast Wyoming and southeast Montana. The PRB is the largest coal producing basin in the United States, responsible for approximately 260 million tons of production in 2022, representing 43.5% of the total national coal production in 2022. The PRB is divided into a northern region, the North Powder River Basin (“NPRB”), and a southern region, the South Powder River Basin (“SPRB”). SPRB coal is a relevant market for assessing the effect of Defendants’ anticompetitive acquisitions because, among other things, SPRB coal has a lower sulfur and sodium content than other forms of coal, which both aids with regulatory compliance and confers other operational benefits on power generation plants that make it preferable to potential substitutes.

67. Fifteen mines operate in the Powder River Basin, with most of the active mining taking place at the 12 mines located in the SPRB in the drainages of the Cheyenne River. Almost all the coal deposits in the Powder River Basin are owned by the federal government. New entry would thus require not only large capital investments in mine equipment, but also obtaining numerous federal and state regulatory approvals.

68. The coal in the NPRB has different characteristics from the coal in the SPRB, which places them into different product markets. Specifically, coal from the SPRB has lower sodium and sulfur content than NPRB coal. The lower emissions that result from its lower sulfur content mean that SPRB coal, compared to NPRB coal, more readily complies with environmental regulations and confers other operational benefits. Power generators also consider the lower sodium content in the ash produced by the combustion of SPRB coal, compared to NPRB coal, to be a desirable property.

69. SPRB coal is likewise distinguishable from coal mined elsewhere in the United States (e.g., the Illinois Basin, the Uinta Basin located in Utah and Colorado, and coal mined in the Appalachian region) based on several factors that are important to electric power producers, including, but not limited to:

a. Low cost of production: SPRB coal is relatively close to the earth’s surface and thus is extracted from surface mines, which generally face lower costs than underground mines. SPRB coal beds are relatively thick, which also reduces the cost of extraction compared to thinner beds. The difference in cost is reflected in the sales price of the coal. Measured in dollars per million British Thermal Units ($/mmBTU) at the mine mouth, SPRB coal is the lowest priced coal in the United States. For example, the United States Energy Information Administration (“EIA”) releases weekly information regarding the spot price of different coals, broken down by coal region. According to the EIA, for the week ending January 12, 2024, on a $/mmBTU basis, the spot price of Central Appalachian coal ($3.24) was more than four times the price of SPRB coal ($.79), and such price differences have been persistent over time.

b. Heat content: SPRB mines yield sub-bituminous coal with a heat content that typically ranges from 7,710 to 9,410 BTU per pound. Electric power generators typically seek to purchase coal with BTU values that fall within a specific range for which their units are designed to operate most cost-effectively, and many electric power generators are designed to operate within this range.

c. Low sulfur content: SPRB coal typically has relatively low sulfur content, and thus when burned produces less sulfur dioxide than higher-sulfur coals.

d. Low sodium content: SPRB coal is also relatively low in sodium compared to other coals mined in the United States.

70. Due to this unique combination of SPRB coal characteristics, coal mined in other basins and in other countries does not meaningfully constrain the price of SPRB coal in the large portions of the United States where SPRB coal can be shipped economically. Power plant generation units that burn SPRB coal rarely switch to coal from a different basin, since doing so would have negative implications for coal purchasing costs, environmental compliance, and the efficiency of power generation. Not only is SPRB coal the lowest-cost coal produced in the United States, but environmental restrictions may prevent SPRB-burning power plants from burning coal with higher proportions of certain pollutants (such as sulfur). In some cases, plant owners may be entirely foreclosed from burning another type of coal because the plant only has regulatory approval to burn SPRB coal. Moreover, many power plants that burn SPRB coal can face substantial switching costs if they attempt to switch to other coals, which could include installation of additional pollution-control equipment.

71. Industry and public recognition confirm that SPRB coal differs from non-SPRB coals. Public sources of information, including analysis of commodity prices, routinely differentiate between SPRB coal and other types of coal. Likewise, market participants and industry analysts regularly discuss supply and demand conditions for SPRB coal separately from supply and demand for other types of coal.

72. SPRB coal prices are typically determined through direct interactions between SPRB coal producers and customers, involving a request-for-proposal (“RFP”) process in which customers solicit bids from multiple suppliers of SPRB coal. Customers typically issue an RFP specifying the quantity of coal that they desire to contract for and the time period in which the coal will be delivered (often one year or two years). Based on responses to the RFP, a customer will negotiate a supply contract with one or more suppliers. While customers can also purchase SPRB coal by placing a bid on the Over-The-Counter (“OTC”) spot market, due to their reliance on regular supplies of large amounts of coal for their coal-fired power plants, most customers prefer to contract with suppliers for most of their SPRB coal purchases rather than rely exclusively or primarily on OTC purchases. SPRB coal customers value the security of supply provided by a contract, and OTC prices are typically higher than individually-negotiated contract prices.

73. Due to the widespread use of RFPs, SPRB coal producers typically know the identity of customers seeking to purchase SPRB coal and can customize their bids based on a customer’s circumstances. For example, SPRB coal producers can take into account the location of the customer’s power plants, which affects both the plants’ regulatory requirements and the shipping costs the customer will incur. SPRB coal purchasers generally negotiate shipping costs directly with railroads, without the involvement of SPRB coal producers, and greater distances typically result in greater shipping costs. Shipping costs are significant compared to the price of SPRB coal at the mine mouth; in many cases, shipping costs account for 50% or more of a customer’s delivered cost.

74. Power generation units designed to burn SPRB coal cannot readily replace SPRB coal with natural gas, wind, sun, or nuclear fuels. Owners of such units cannot practicably construct new facilities that use alternative fuels in response to a small-but-significant increase in the price of SPRB coal because it is expensive and time-consuming to construct new facilities powered by natural gas, renewables, or nuclear fuels.

75. Some power plants that rely on SPRB coal are owned by utilities that can also supply electricity to end customers by (i) generating it from power plants designed to use fuels other than SPRB coal, and (ii) purchasing power “wholesale” from other power generators. Yet, if SPRB coal prices were to increase by a small-but-significant amount, such utilities are unlikely to reduce their purchases of SPRB coal by enough to render the price increase unprofitable for a hypothetical monopolist, for several reasons, including:

a. Coal-fired power plants are expensive to construct (modern plants can cost more than $1 billion), and once a power plant operator has made such a significant investment, it has strong incentives to operate its plant, even if the price of coal increases by a small-butsignificant amount;

b. Electricity producers often rely on coal-fired power units to run continuously to reliably supply power despite variable conditions (such as weather, natural gas pipeline constraints, and electricity grid congestion) that can render alternative power sources unreliable or unavailable;

c. Coal-fired power units are usually run continuously to optimize emission controls and minimize pollution in compliance with applicable regulations and permits. Boiler flame stability plays a critical role during coal combustion in reducing nitrogen dioxide, a “criteria” pollutant under the Clean Air Act, 42 U.S.C. § 7408; 40 CFR § 50.11; and,

a. A small-but-significant increase in SPRB coal producers’ prices would have only a minor impact on a power generator’s cost of producing electricity, due to the high transportation costs of SPRB coal and other factors. Indeed, as the district court found in Federal Trade Commission v. Peabody Energy Corporation, “SPRB coal customers are … different from customers in many other industries” to the extent that they “are legally obligated to provide electricity to their customers” and “cannot simply choose to not reach a deal but rather must generate electricity—including from SPRB coal, if their EGUs are designed to burn it—in order to meet those obligations.” 492 F.Supp.3d 865, 892 (E.D. Mo. 2020) (cleaned up).

76. The foregoing paragraphs establish that a hypothetical monopolist of the SPRB coal product market would profit from a small but significant and non-transitory increase in price, and that there is thus a distinct product market for SPRB coal.

77. Moreover, although the price of natural gas has some impact on the price of coal, the existence of competition with natural gas producers does not undercut the existence of an SPRB coal market. SPRB coal has distinct customers with distinct needs because these customers have “SPRB-fueled power plants, which are long-lived, expensive, and configured for SPRB coal’s distinct characteristics.” FTC v. Peabody Energy, 492 F. Supp. 3d at 898. As the Court determined in FTC v. Peabody Energy, in upholding the FTC’s SPRB product market definition, there is “little doubt that SPRB coal providers compete … among themselves in a market for SPRB coal.” Id. at 896. The same holds true for the Thermal Coal product market.

78. Although the price of renewable energy may have some impact on the price of SPRB or Thermal Coal, the existence of such price competition does not suggest that renewable energy sources are in the same product market. Renewable energy sources are intermittent and non-dispatchable, “meaning they only generate energy when wind is blowing or the sun is shining, which is out of a utility’s control.” Id. at 879. As the Court found in FTC v. Peabody Energy, “this constraint makes renewable fuels imperfect replacements for fossil fuels like coal.” Id.

There is a Relevant Product Market for Thermal Coal

79. Of the 594.2 million tons of coal produced during 2022, 532.3 million tons were sold in the market for thermal coal. Of those 532.3 million tons of coal marketed as thermal coal, 39.5 million tons were exported, representing 45.9% of total U.S. coal exports, while 492.8 tons were sold to domestic U.S. customers.

80. Thermal coal is burned to generate steam for the production of electricity or for process heating purposes or is used as a direct source of process heat for various industrial uses.

81. Thermal coal is used in the industry to refer to all coal that is not classified as metallurgical coal. Metallurgical coal must have a sufficiently high heat, low ash, and low sulfur content to form a coke that can be used in a blast furnace. Metallurgical coal is significantly purer and has a significantly higher energy density and carbon content than thermal coal. Thermal coal, which lacks the energy density, high carbon content, and high purity that is needed for the production of coke, is not a substitute for metallurgical coal. The cost of metallurgical coal is thus significantly higher than the cost of thermal coal and the price of thermal coal is not significantly constrained by the price for metallurgical coal.

82. Unlike the Coal Companies, which have multi-billion-dollar market capitalizations and substantial proven reserves, privately-held thermal coal producers are often smaller, family-owned mines. These smaller market participants would, in response to a sudden price increase, lack the capacity and the capital that they would need to increase production significantly. And even those privately-held firms that possess the proven reserves and have been granted the regulatory approvals that would permit them to increase capacity would find it difficult to obtain the financing they would need to increase their output, for banks have been under increasing pressure, including from Defendants, to deny funding to coal miners and other fossil fuel companies.20

83. A small but significant and non-transitory increase in price would not cause the operators of power plants designed to burn thermal coal to switch away to alternative sources of fuel.

a. Both the substantial costs that would have to be incurred to design and construct a new power plant, and the substantial time that would be required to bring that plant into operation, mean that an operator of a coal-fired power plant has strong incentives to continue to operate its plant even if the price of coal increases by a small-but-significant amount;

b. The substantial costs that would be incurred to redesign a coal-fired power plant to use an alternative fuel source mean that an operator of a coal-fired power plant has strong incentives to continue to operate its plant even if the price of coal increases by a small-but-significant amount;

c. Finally, electric power generators are legally obligated to provide electricity to their customers, and therefore, if they cannot reach a deal with their suppliers of coal, they must still obtain the coal they need to generate that electricity. Peabody Energy Corp., 492 F.Supp.3d 865, 892 (E.D. Mo. 2020).

84. The foregoing paragraphs establish that a hypothetical monopolist of the Thermal Coal product market would profit from a small but significant and non-transitory increase in price, and that there is thus a distinct product market for Thermal Coal.

The Relevant Geographic Markets

85. The SPRB constitutes not only a relevant product market, but a relevant geographic production market. The suppliers of SPRB coal are located exclusively within the Southern Powder River Basin, and this is the region in which purchasers of SPRB coal can seek alternative suppliers of SPRB coal.

86. The United States also constitutes a relevant geographic market in which to analyze the competitive effects of Defendants’ acquisitions on SPRB coal. SPRB coal is not sold in any significant quantities outside the United States, and even if it were, due to high transportation costs, SPRB coal customers could not defeat a price increase by purchasing SPRB coal outside of the United States and reimporting it.

87. The United States also constitutes a relevant geographic market in which to analyze the competitive effects of Defendants’ acquisitions of thermal coal. While thermal coal is sold in significant quantities outside of the United States, due to the high transportation costs, consumers of thermal coal could not defeat a price increase by purchasing coal abroad and importing it to the United States.

88. Alternatively, relevant geographic markets could be defined based on the locations at which SPRB coal is consumed. All or nearly all SPRB coal consumed is burned at fewer than 150 power plants; the majority is consumed by power plants located in the central United States and upper Midwest, within the states of Arkansas, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Louisiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Texas, Wisconsin, and Wyoming. Defendants’ conduct substantially lessens competition for the sale of SPRB coal within a relevant geographic market consisting of one or more of the locations at which SPRB coal is consumed.

DEFENDANTS’ ACQUISITIONS OF STOCK POSE A SUBSTANTIAL THREAT TO COMPETITION IN THE RELEVANT MARKETS

89. Defendants’ acquisitions of stock have given each of them the power to influence the management of their portfolio Coal Companies.

90. When a shareholder who holds 15%, 12%, 8%, or even 3% of a company’s outstanding shares speaks, management listens. The SEC has drawn a bright line at 5%, requiring investors to file a Schedule 13D declaring whether they intend to actively exercise influence over a company’s management no later than 10 days after their ownership interest exceeds that level. 21 The financial news is replete, however, with stories of activist investors who hold as little as 1% or 2% of a company’s shares successfully seeking seats on the company’s board of directors, or demanding that management cut costs or chart a new course for the business. For example:

a. In 2023, activist investor Carl Icahn succeeded in getting a nominee elected to the board of directors of gene-sequencing giant Illumina and knocking the company’s chairman off the board; Icahn owned 1.4% of the company’s shares.22

b. In 2021, Engine No. 1 waged a six-month campaign to change Exxon Mobil’s “role in a zero-carbon world,” ending in a proxy fight that resulted in its obtaining three seats on the company’s board of directors; Engine No.1 owned a mere 0.02% of Exxon’s outstanding shares, but its campaign succeeded largely through votes from BlackRock, State Street, and Vanguard.23

c. In 2017, Nelson Peltz’s Trian Fund won a seat on the board of directors of Proctor & Gamble after a hotly contested proxy fight; Trian owned roughly 1.5% of the company’s shares.24

d. In 2017, Third Point successfully lobbied the board of directors of Nestle to increase the company’s dividends and buybacks, and to sell off its skin health unit and its U.S. ice cream business. Third Point had acquired 40 million shares of the company, representing 1.3% of the company’s outstanding 3.09 billion shares.25

e. In 2014, Starboard Value launched a proxy fight that resulted in the replacement of the entire board of directors of Darden Restaurants; Starboard held an 8.8% stake in the company.26

91. Even an “unsuccessful” proxy campaign can ultimately influence the board of directors to adopt the policy or pursue the course of action for which a significant shareholder was advocating. For example, in 2015, Nelson Peltz, whose Trian Fund controlled 2.7% of DuPont’s stock, waged an unsuccessful proxy campaign for four seats on the board of directors in an effort to influence the company to split itself up into separate businesses.27 But within a year, DuPont had replaced its CEO and agreed to merge with Dow Chemical to create a conglomerate that would be broken up into three companies.28

92. The power to influence a single company’s output or pricing decisions would ordinarily pose only an insignificant risk to competition. In a properly functioning market, when one company cuts output, its competitors will increase production in order to capture that new market share. Every competitor will, in other words, vigorously compete to maximize its profits, thereby making the output reduction of a single competitor unprofitable.

93. The dynamic changes when a single owner obtains a significant ownership percentage of multiple competitors across a single market with only a handful of competitors. When a shareholder is among the largest shareholders not only of nearly every major company in an industry but also of the banks and investment firms that finance that industry, that shareholder has the power to influence the entire industry. Quite simply, “[w]hen BlackRock Chairman Larry Fink speaks, the investment world tends to listen.”29 Congress enacted Section 7 of the Clayton Act to address the threat to competition that attends when such a single shareholder acquires directly or indirectly the stock of multiple horizontal competitors.

94. Each Defendant’s ownership of the Coal Companies creates the sort of anticompetitive arrangement that Section 7 forbids. Each Defendant’s substantial shareholdings enable it to, among other things, (a) access sensitive business information, (b) coerce management to adopt specific coal production targets, (c) force management to adopt disclosure policies that would permit Defendants to monitor their compliance with those targets, (d) seek the appointment or removal of members of the boards of directors of these companies to further Defendants’ production and disclosure goals, (e) present and obtain approval of shareholder proposals to reduce coal production, and (f) otherwise influence corporate policies adopted by the firms in which Defendants have acquired substantial common ownership stakes. Such practices limit competition between the competing firms.

95. This power to influence management means that Defendants’ partial acquisitions of the shares of these horizontal competitors in the coal industry pose a similar risk to competition as an outright merger of those competing coal producers. When competing firms are effectively brought under common control, those firms—though competitors in name—experience significantly reduced incentives to compete against one another, especially when their common shareholders are active in corporate governance and actively voting for changes in management.

96. The Justice Department and Federal Trade Commission’s 2010 and 2023 Merger Guidelines, the federal courts, and leading antitrust scholars all agree that partial acquisitions of stock across competing firms must satisfy the same legal standards as mergers and acquisitions of those firms. See, e.g., DuPont, 353 U.S. at 586 (DuPont’s partial acquisition of a 23% interest in General Motors in 1917-1919 violated Section 7 because of the incentive it created in 1949 for General Motors to purchase finishes and fabrics from DuPont). 30 Indeed, the 2023 Merger Guidelines advise using the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (“HHI”) to measure the effect of such acquisitions on market concentration. See Merger Guidelines: U.S. Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission at Guidelines 1 & 11 (Dec. 18, 2023), https://bit.ly/3BgNlE4 (“2023 Merger Guidelines”). “To be sure, control or steps toward control or toward total ownership are tested in the usual manner to see whether there is a reasonable probability of a substantial lessening of competition,” while “[t]esting for the prohibited effect is much more subtle … when control is neither attained nor contemplated.” DONALD F. TURNER & PHILLIP AREEDA, ANTITRUST LAW: AN ANALYSIS OF ANTITRUST PRINCIPLES AND THEIR APPLICATION ¶1203a (1978). As set forth below, Defendants have attained and exercised a degree of control over the Coal Companies that has been more than sufficient for Defendants to set and enforce common policies that substantially reduce competition across the entire coal industry.

97. Market concentration is ordinarily measured using the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index. The HHI for a relevant market is calculated by squaring the percentage market shares of each producer that sells the relevant product within the relevant geographic market and totaling those figures. The post-acquisition HHI and the change in HHI—post-acquisition compared to pre-acquisition—are used to determine whether an acquisition of shares is likely to significantly restrain competition and therefore raises competitive concerns. An acquisition is presumed likely to create or enhance market power—and is thus presumptively illegal—when the post-transaction market’s HHI exceeds 1,800 and the transaction increased the HHI by more than 100 points. The same structural presumption applies when a merger transaction or joint venture creates a firm with a market share greater than 30% and a change in the HHI greater than 100 points.

98. HHI is typically applied to acquisitions that result in complete control, to what has been described as “a special case of a ‘partial’ investment of 100 percent that gives the acquiring firm complete control.”31 While the antitrust enforcers have made clear that partial acquisitions are subject to the same legal standard as any other acquisition, 32 Defendants’ partial acquisitions do not confer “complete control,” and will therefore require a more nuanced assessment of the degree of control or influence that these partial owners exercise over management and how this influence translates into competitive effects. Thus, unlike most merger analysis, a central part of the analysis of partial ownership is an assessment of which owners have what type of control over the corporation and how this control translates into management decisions. HHI thus offers a rough approximation of the effect that substantial partial acquisitions have on markets.

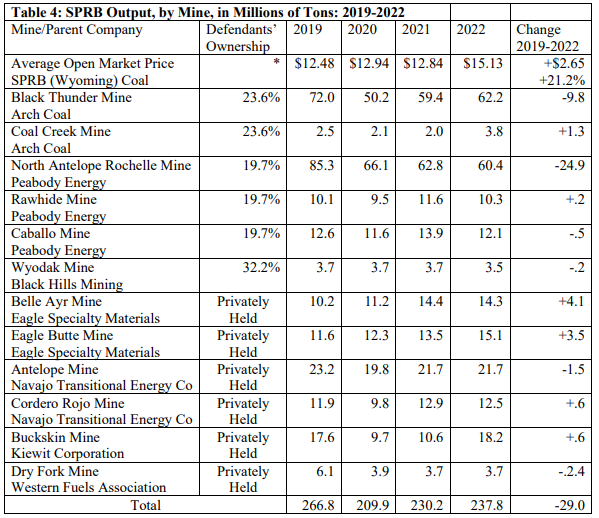

99. SPRB Market Concentration. There are 12 mines currently operating in the SPRB. In 2022, they produced a total of approximately 240 million tons of coal, representing 40.4% of total U.S. coal production, 45.1% of U.S. thermal coal production, and 100% of U.S. SPRB coal production.33 As measured by the HHI, and without accounting for the effects of Defendants’ stock acquisitions, the SPRB market would have had a concentration of 2,360.6.

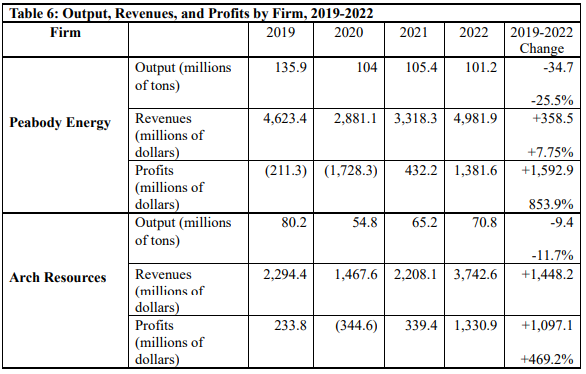

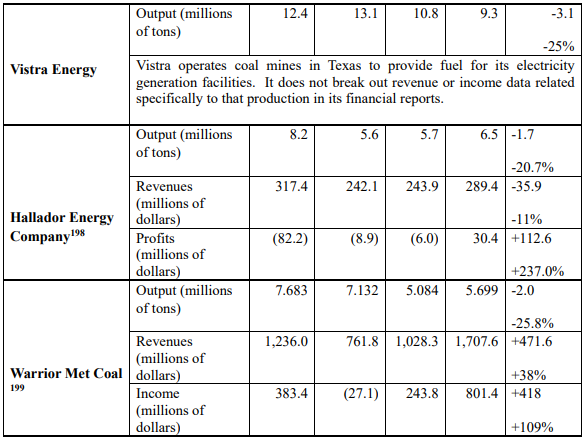

100. Defendants have acquired shares that represent between 30.43% and 34.19% of the stock of the three companies that control six of these 12 mines. See below Table 2. These six mines were responsible for approximately 63% of the SPRB coal produced in 2022.

101. Were these three coal-producing firms formally to merge, create a joint venture, or otherwise come under common control, it would result in a market concentration of approximately 4,524—an increase in the HHI of 2,115. Such a transaction would be presumptively unlawful. The market share of that firm or joint venture would also be 64%—far higher than the 30% required to apply the structural presumption under the Merger Guidelines.

102. The effect on competition is no different when Defendants use their substantial stock acquisitions to coordinate a reduction in the production of SPRB coal by these three firms. And as demonstrated below, this is exactly what Defendants have used their shares to accomplish, with precisely the effects on competition that the economic models undergirding the HHI would predict.

103. Defendants’ reduction of competition is particularly acute because one of the privately held coal producers in which Defendants have no ownership stake does not supply its coal to the open market. The Dry Fork Mine is operated by a cooperative organization of power plant owners known as the Western Fuels Association and is a vertically-integrated company that has fully committed its SPRB production to supplying its own captive power plant.

104. The other three producers are Navajo Transitional Energy Company, LLC, Eagle Specialty Materials, and Kiewit Corporation. These companies lack the financial resources and the capacity to increase their output at sufficient scale to offset the decreased output by the coal producers in which Defendants have an ownership stake.

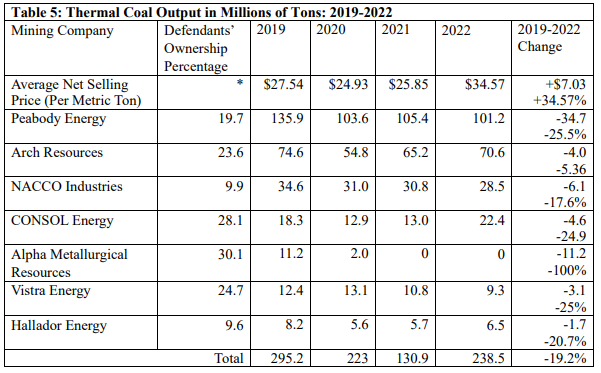

105. The National Market for Thermal Coal. The Coal Companies are collectively responsible for 240.8 million tons of the nation’s total output of 523.3 million tons of thermal coal, or 46% of the national output. The HHI generated by these eight companies standing alone would be 521.96.

106. Were the Coal Companies to merge or form a joint venture, the combined firm would yield an HHI for the thermal coal market of 2,116.0—an increase of 1,594. Such a transaction would be presumptively unlawful. The market share of that firm or joint venture would also be 46%—again far higher than the 30% required to apply the structural presumption.

107. The effect on competition is no different when Defendants use their substantial stock acquisitions to control these eight firms and induce them to implement a common policy concerning price or output. And as demonstrated below, that is exactly what Defendants have used their shares to accomplish, with precisely the effects on competition that the economic models undergirding the HHI would predict.

108. Defendants’ acquisition of substantial shares in the Coal Companies also significantly increases the risk of coordination between the Coal Companies in each of the relevant markets. As major shareholders in the dominant competitors in the relevant markets, Defendants have direct access to the management of each of those competing firms and thus the ability to transmit information across competitors. And Defendants in fact used that privileged access to communicate their output reduction scheme to each of the Coal Companies and then to monitor and police compliance with the scheme. By acquiring substantial partial interests in these competitors in the coal industry, Defendants made collusion possible—a possibility that has in fact been realized.

109. Defendants’ acquisitions of the stock of the Coal Companies also significantly increases the risk of substantially lessening competition by diminishing the incentive for management of those firms to compete to win market share from each other. It creates a contrary incentive for management to maximize the aggregate profits of the entire industry—not of their individual firms—and thus the overall profits of their common owners. As the academic literature explains, when a shareholder owns stock in a single firm, maximizing the profits of that firm maximizes the profits of that shareholder; but when that shareholder owns stock in all the firms that compete in an industry, maximizing the profits of the entire industry maximizes the profits of the shareholder.38 Thus, when management knows their firm is owned by so-called “horizontal shareholders”—i.e., by shareholders who own shares in the competing firms across an industry— management has an incentive to maximize the profits of the industry. In other words, the incentive is to operate as a cartel.

110. For the same reasons, Defendants’ acquisitions and holding of the stock of the Coal Companies significantly increases the risk that competition will be substantially lessened by removing the incentives these firms would otherwise have to disrupt efforts by their competitors to coordinate.

111. In addition, Defendants’ acquisitions and holding of the stock of the Coal Companies significantly increase the risk that competition will be substantially lessened by decreasing the incentive for management of those firms to compete with alternative fuel sources. Defendants own substantial interests not only in domestic thermal coal producers but in competitors to thermal coal like natural gas and alternative energy. Indeed, BlackRock alone has invested $170 billion in U.S. energy companies—including oil and gas producers, alternative energy producers, and pipeline operators.39 Vanguard, BlackRock, and State Street are the three largest shareholders of Exxon Mobil, owning 988 million shares or 22% of the outstanding shares40; of Chevron, 413 million shares, or 22.4%41; of Devon Energy, 170 million shares, or 27%;42 of First Solar, 29 million shares, or 27%43; and NextEra Energy, 454 million shares, or 22%.44 For each of these companies, Vanguard is the largest shareholder, followed closely by BlackRock, with State Street coming in third. These companies—and by extension their shareholders, including Defendants—would all benefit from eliminating lower-cost alternative energy sources. On that dimension, too, Defendants’ common ownership thus creates an incentive for the Coal Companies not to compete aggressively against more expensive alternative forms of energy.

112. For all these reasons, it is likely that Defendants’ acquisitions of the stock of the Coal Companies, standing alone, poses a risk to competition in the domestic coal markets sufficient to warrant their prohibition under Section 7 of the Clayton Act. But as set forth below, this threat to competition is not just hypothetical or merely probable—it has actually come to pass. Defendants have, in fact, already used their shares, by proxy voting and otherwise, to bring about the substantial lessening in competition in the domestic coal markets that Section 7 forbids. The most compelling proof that Defendants’ acquisitions may substantially lessen competition, in other words, is that Defendants’ acquisitions have already done so.

DEFENDANTS AGREED TO A COMMON STRATEGY TO REDUCE OUTPUT

113. While common ownership of horizontal competitors poses an inherent threat to competition, the Congress that enacted Section 7 of the Clayton Act recognized that, so long as even a large shareholder remains passive and does not seek to use its shares to influence management, then the threat that shareholder poses to competition remains hypothetical.

114. Section 7 accordingly does “not apply to persons purchasing such stock solely for investment and not using the same by voting or otherwise to bring about, or in attempting to bring about, the substantial lessening of competition.” 15 U.S.C. § 18. Should a shareholder abandon a passive investment strategy, however, and seek to bring about a substantial lessening of competition, then that shareholder no longer enjoys this safe harbor.

115. In 2021, Defendants each publicly announced their commitment to “[i]mplement a stewardship and engagement strategy, with a clear escalation and voting policy, that is consistent with our ambition for all assets under management to achieve net zero emissions by 2050 or sooner.”45 The organization that Defendants joined made clear that for assets to be in line with net zero, they must align with the International Energy Agency Roadmap to Net Zero,46 which required the CO2 emissions from coal to drop over 58% between 2020 and 2030.47 Given that there is no realistic path for a coal company to cut coal emissions other than by cutting production, Defendants announced their intent to adopt a strategy consistent with net zero and “with a clear escalation and voting policy” to push the coal companies in their portfolio to cut output by more than half by 2030. BlackRock and State Street also joined Climate Action 100+, which expressly stated its view that “the IEA’s NZE requir[es] a reduction of 50% in thermal coal production by 2030 versus 2021.”48 There are few, if any, acts likelier to substantially lessen competition than an industrywide output reduction scheme organized and policed by shareholders with the ability to monitor compliance and the power to discipline the management of any individual company that deviates from the restrictions Defendants set.

116. Defendants BlackRock, State Street, and Vanguard announced their common commitment to this scheme by joining the Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative; Defendants BlackRock and State Street further committed themselves to achieving these aims by becoming signatories to Climate Action 100+. Defendants’ open participation in these initiatives provides substantial evidence of a horizontal agreement among Defendants to use their common ownership of the Coal Companies to set and enforce output restrictions on coal that have impacted the entire industry.

Climate Action 100+ Presents Compelling Evidence of Defendants’ Agreement to Seek Coordinated Reductions in Coal Production

117. Climate Action 100+ (“CA 100+”) is “an unprecedented global investor engagement initiative” that targets companies in the energy industry and other sectors to ensure they “take necessary action on climate change.”49 Signatories to CA 100+ commit to influencing corporate policies and ensuring that firms: (1) “[t]ake action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions across the value chain in line with the overarching goals of the Paris Agreement”; (2) “[i]mplement a strong governance framework which clearly articulates the board’s accountability and oversight of climate change risks and opportunities”; and, (3) monitor compliance with carbon output reduction targets by “[p]rovid[ing] enhanced corporate disclosure in line with the recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD).”50

118. CA 100+ has not been vague or evasive about its intentions for the coal industry. As explained in CA 100+’s “Investor Expectations for Diversified Mining,” “[a]s the most emission-intensive fossil fuel, [coal’s] reduction is prioritised in climate modelling with the IEA’s NZE requiring a reduction of 50% in thermal coal production by 2030 versus 2021, and 91% by 2050.”51 These benchmark reductions are aligned with limiting global temperature increases to 1.5⁰C.

119. CA 100+ and its members openly committed to working together to induce these dramatic reductions in the production of coal. CA 100+ established “alignment metrics” that set specific target reductions for coal production. These metrics require medium term reductions in thermal coal production of 50% between 2021 and 2030, Alignment Metric 5.v.e, and 91% between 2021 and 2050, Alignment metric 5.v.d.52

120. CA 100+ candidly admitted that its members were not going to reach their “decarbonization” goal without reducing coal production—especially the production of thermal coal—by the mining industry: “[T]he mining sector and its value chains will also need to decarbonise. For some commodities, this means reducing production. In net zero scenarios, coal production declines towards zero, with thermal coal declining faster than metallurgical coal.”53 Anne Simpson, CA 100+’s investor representative for North America explained in 2021, “[w]e’re not going to get to net zero by just bringing down the supply of oil, gas and coal.”54 Bringing down the supply is the sine qua non of the CA 100+ agenda.

121. CA100+ members agreed to work with the coal companies in which they had invested to obtain commitments to disclose their “planned thermal coal production factored into its short, medium, and long-term targets (expressed in unit Mt or TJ) and either a % or absolute change from a stated base year value.”55

122. CA 100+ members agreed to work to obtain commitments from the companies in which they have acquired shares to disclose their Scope 3, category 11 emissions.56 In the case of thermal coal, disclosures of Scope 3, category 11 emissions would reflect the total lifetime carbon emissions that would be generated by the consumption of that coal.57 When a company knows the total lifetime carbon emissions that the thermal coal a company plans to produce will cause, it knows the total amount of thermal coal that competitor is planning to produce. These disclosures would thus alert a company’s competitors to the company’s future production targets and enable Defendants and the companies’ competitors to police the disclosing company’s ongoing compliance with those targets.

123. CA 100+ members agreed to use their shareholdings to pressure companies to meet these “decarbonization” goals. Mindy Lubber, CA 100+’s investor network representative for North America detailed how CA 100+ members will identify leading competitors in an industry, with the expectation that other competing firms will follow suit and follow the same practices: “Fundamentally companies compete, and when one company in a sector takes action, the others usually follow.”58

124. Resistance by management was futile because, as Ms. Lubbers continued, “[i]f companies aren’t willing or able to respond to the challenge of moving towards a net zero transition, we will look for new leadership. … There may be board directors who don’t feel compelled or have the expertise to get this transition done – but they must then make way for those that do. This is concentering [sic] minds in boardrooms and across the investor community and is a new, welcome dynamic to engagement and stewardship.”59

125. CA 100+ provided its signatories with a roadmap for using their shareholdings in coal producers to influence corporate governance at each of these firms to ensure that each of these companies would simultaneously be reducing their output of coal to achieve the same level of output reduction and would report on their ongoing compliance with these targets to their common shareholders. CA 100+ signatories were agreeing, in effect, to organize and police an output reduction cartel, to play the role of the hub in a hub-and-spoke reduction arrangement.

126. In 2020, Defendant BlackRock and Defendant State Street became signatories to Climate Action 100+ (“CA 100+”).

127. Defendant BlackRock became a signatory of CA 100+ on January 9, 2020.60

128. Defendant State Street announced that it had joined CA 100+ on November 30, 2020, formally committing itself to the initiative’s central goals of “improving governance of climate change, reducing emissions, and strengthening climate-related disclosure.”61 State Street simultaneously announced that it would continue to advocate for those goals “through company engagement[], [State Street’s] thought leadership, and proxy voting.”62

Defendants’ Participation in the Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative is Compelling Evidence of Defendants’ Agreement to Seek Coordinated Reductions in Coal Production

129. In 2021, BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street also became signatories to the Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative.

130. Signatories to the Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative committed to achieving the same goals that the signatories to CA 100+ agreed to pursue—namely net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 and achieving “decarbonisation goals” consistent with reaching net zero emissions by 2050 (or sooner) across all assets under management.63

131. As with CA 100+, signatories to the Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative commit to setting interim reduction targets to be achieved by 2030. These targets are to be consistent with limiting global warming to 1.5⁰C by 2050 and embrace the same International Energy Agency Roadmap to Net Zero that is the basis for the 2030 and 2050 reduction targets discussed above.64 The signatories to the Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative specifically commit to phasing out coal investments: “Notably, this includes immediately ceasing all financial or other support to coal companies* [sic] that are building new coal infrastructure or investing in new or additional thermal coal expansion, mining, production, utilization (i.e., combustion), retrofitting, or acquiring of coal assets.”65

BlackRock

132. On March 29, 2021, Defendant BlackRock became a signatory to the Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative (“NZAM”). 66

133. As part of its commitment to NZAM, BlackRock published its initial target disclosure on May 1, 2022.67 That disclosure revealed that BlackRock had committed to manage 77% of its $7.3 trillion of assets under management in compliance with its commitment to NZAM, and anticipated that “at least 75% of BlackRock corporate and sovereign assets managed on behalf of clients [would] be invested in issuers with science-based targets or equivalent.”68

134. BlackRock further explained that it “expect[ed] to remain long-term investors in carbon-intensive sectors like traditional energy,” and had adopted a strategy of “engag[ing] with companies.” 69 In 2020, it first focused on 440 public companies that contributed 60% of Scope 1 and Scope 2 greenhouse gas emissions,70 and then, in 2021, it expanded that universe to 1,000 carbon-intensive public companies responsible for 90% of those emissions.

135. After joining NZAM, Defendant BlackRock, acting through the subsidiaries, affiliates, and investment trusts it manages and over which it exercises control, acquired even more shares in, and greater influence over, the Coal Companies.

136. Defendant BlackRock was not reluctant to use that growing influence. It further announced that it would discipline management that failed to satisfy its demands, both when voting on shareholder proposals and by voting to remove management: “[w]here we do not see enough progress for these issuers, and in particular where we see a lack of alignment combined with a lack of engagement, we may not support management in our voting for the holdings our clients have in index portfolios, and we will also flag these holdings for targeted review and engagement in our discretionary active portfolios where we believe they may present a risk to performance.”71 BlackRock also helped lead a “workstream on Managed Phaseout of High-emitting Assets” that called for the “early retirement of high-emitting assets” such as coal mines.72

Vanguard

137. Defendant Vanguard became a signatory to the Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative on March 29, 2021. 73

138. In December 2021, Vanguard published a report outlining its “expectations for companies with significant coal exposure.”74 The report stated that “shareholder proponents have used the proxy voting system to,” among other things, “ask companies to shutter or divest their coal assets, or persuade financial institutions to stop providing financial services to the thermal coal industry and the entities that extract thermal coal from the ground.” 75

139. “Vanguard’s Investment Stewardship team,” the report continued, “has engaged with companies in carbon-intensive industries, and their boards, over the last several years and has discussed,” among other things, “shifts in supply and demand…,”76 and seeking to “understand how companies set targets in alignment with these goals” of the Paris Agreement and the Glasgow Climate Pact.77 Specifically, Vanguard sought “clear disclosures” from management of firms in the coal industry, including an “[e]xplanation of how thermal coal remains relevant for a company’s customer base and the market it serves over 10, 20, and 30, years.”78

140. Defendant Vanguard also announced that it would require “[e]ffective disclosure[s]” by those firms operating in the thermal coal industry of their compliance with these targets “to allow the market to accurately price securities.”79

141. Defendant Vanguard also announced that it would discipline management that failed to meet its demands, both when voting on shareholder proposals and by voting “against directors who, in our assessment, have failed to effectively identify, monitor, and manage material risks and business practices that fall under their purview based on committee responsibilities.”80

142. As part of its commitment to the Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative, Defendant Vanguard published its initial target disclosure on May 1, 2022.81 The disclosure revealed that Vanguard had committed to managing $290 billion of its assets in line with net zero targets and had established a target of having each of its investment strategies have at least 50% of its market value invested in companies with targets that are consistent with a net zero glidepath by 2030. Defendant Vanguard stated that it had committed to “meaningful engagement with portfolio companies on climate risk across both [its] actively managed and index-based products …” and that its “investment stewardship team will continue to engage with companies about their commitments” to meet emission reduction goals.82

State Street

143. Defendant State Street became a signatory to the Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative on April 20, 2021.83

144. As part of its commitment to the Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative, Defendant State Street published its commitment statement and initial target disclosure on May 1, 2022.84 The Commitment Statement pledged State Street to obtaining a 50% reduction in financed Scope 1 and 2 carbon emissions (i.e., emissions for which a firm is directly and indirectly responsible) intensity by 2030 from the companies in which it invests, relative to their 2019 baseline, and “90% of financed emissions in carbon-intensive industries in the client portfolios in our Net Zero Target Assets… to be coming from companies [that are] achieving net zero, []aligned to net zero or [are] subject to engagement and stewardship actions.”85

145. State Street announced, as its specific “[p]olicy on coal and other fossil fuel investments,” that it “believe[s] engagement and stewardship efforts to be the most effective tool to achieve long-term progress on energy transition.”86